Civil rights attorney Harvey Silverglate has renewed his decades-old call to abolish the FBI. Sound radical? Wait until you learn how the agency has illegally weaponized its internal protocols to turn innocent witnesses into dangerous informants – blackmailing congressmen and even sitting U.S. presidents to entrench a culture of abuse within a black box of power.

Who does the FBI answer to? Certainly not you and me.

Harvey and I discuss how the agency undermines the founders’ design for federalism, and how the oversized Federal Criminal Code allows them to take politicians – along with everyday citizens – hostage.

LINKS:

Three Felonies a Day: How the Feds Target the Innocent by Harvey Silverglate (2011)

Transcript

Bob Zadek: I'm the last generation to have grown up being entertained by radio drama, including as I recall G-Men, where in 30 minutes per episode, an FBI agent eliminated yet another bad guy from harming us. Early television brought us FBI starring Dick Wolf, which ran from around 1965 through around 1974. I entered adulthood thanking heaven that the FBI had our backs. Based on the behavior of the FBI during most of my adult life, I found that I have been brainwashed, as demonstrated by the FBI's treatment of Martin Luther King, Aretha Franklin, hippies in general, the Steele dossier, Hillary Clinton's emails, Hunter Biden's laptop. Need I go on?

Today's guest, Harvey Silverglate, has a perfect solution. Abolish the FBI. Harvey, Welcome to the show.

Harvey Silverglate: Good to be here.

The Dangers of a Federal Police Force

Bob Zadek: Okay, Harvey, you have made a career out of preserving others' civil liberties. You have done a thankless and effective job through the entire career as I understand it. Among your successes, your triumphs, you have given me a nonprofit organization to which I happily give every penny that I can muster, which is FIRE, the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, which protects those who are denied due process, in campuses. You also have litigated against the government in general, the FBI in particular. So, you will give us today the benefit, not only of your general knowledge of how stuff works but also your firsthand sensory perceptions, what you have experienced in protecting those who most need protection against the abuses of government.

As I said in my intro, the FBI always wore suits and ties. They rarely used their guns. They always dressed impeccably. They were polite. They didn't smoke, drink, womanize, or at least that's what the media taught us. They were personified most recently by Kevin Costner’s portrayal of Eliot Ness in that great movie, The Untouchables. He was as pure as new-fallen snow. But yet, you don't quite agree with the media presentation of the FBI, and no doubt, the FBI had a hand in the scripts of those shows (I don't know that for sure).

Why are you now in your writings and have been for some time hoping for encouraging the FBI be abolished? Tell us the headline of what's wrong with the FBI and then we're going to drill very deeply into the specifics.

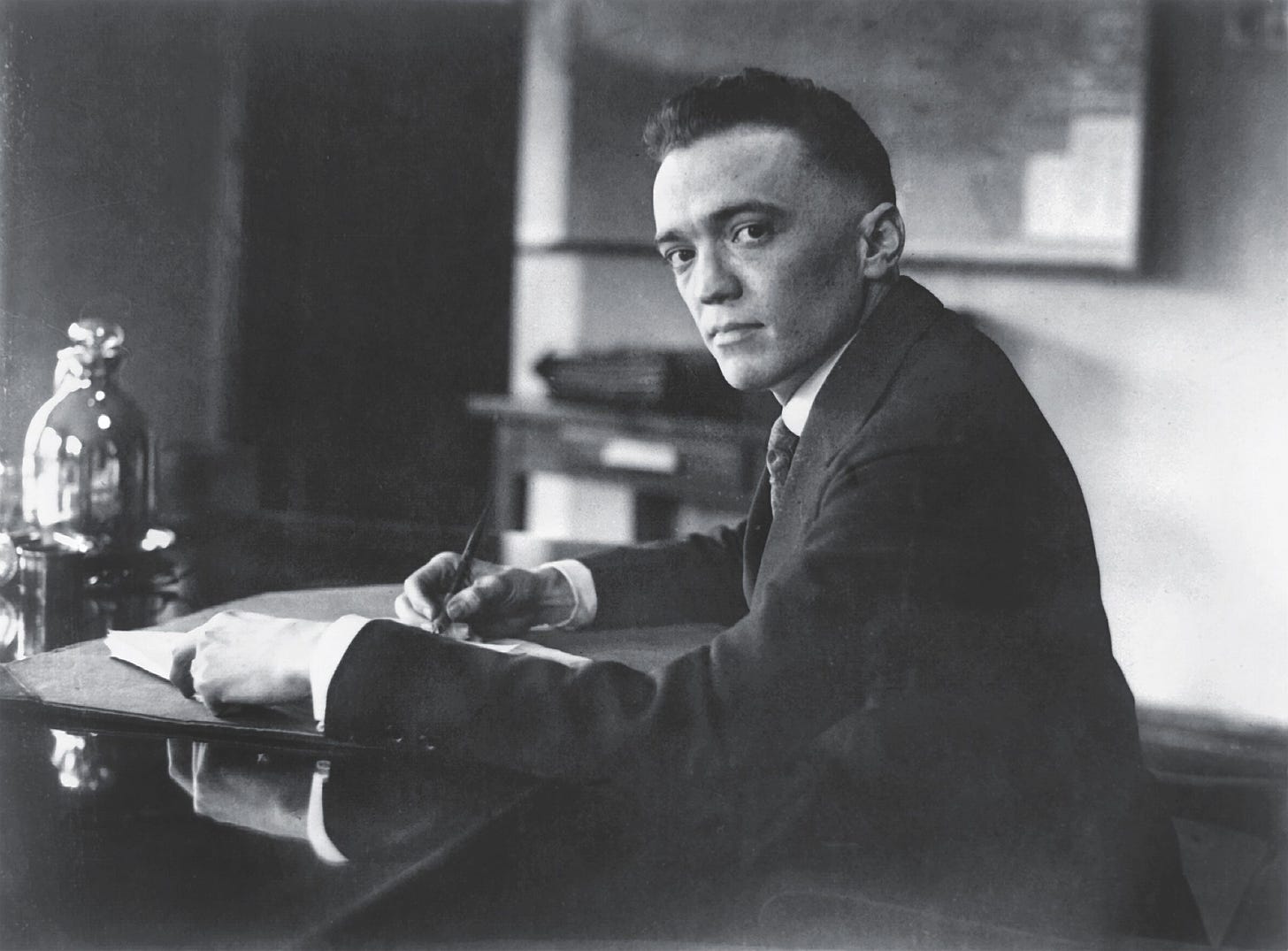

Harvey Silverglate: Culture is everything. The FBI has had a culture that started with its first director, J. Edgar Hoover. Hoover spent his life as the director of the FBI. It went on for decades, and that culture cannot be changed – cannot be reformed. It doesn't matter who the President is, it doesn't matter whom the President appoints as Director of the FBI, it doesn't matter who the Attorney General is. The FBI has an ingrained culture that cannot be changed. My recommendation is that it be abolished. And if a federal police agency is needed – and that's questionable – there should be a new organization with a new name, new agents, and a new director. There should be strict regulations governing the obligation of that new agency to honor the civil liberties of the people that it supposedly is serving and protecting.

Bob Zadek: Now, Harvey, you said about a semester's worth of content just then. One of the words that I picked up on, you said, "If we need a federal police force," you use the word, "police." And you said, "If we need one." That invites an analysis into what the FBI actually is. We, as a country, pride ourselves on never having had a federal police force, the very words you used. The name of the FBI doesn't have police in it. Federal Bureau of Investigation. One might think their job is fact gatherers. They gather information, so other parts of the federal government can use that to enforce, create, and eliminate federal law.

Do you use the word 'police' as suggesting what the FBI is on an informed basis because you really know what they do? Or was it just a word that may not have been intended?

Harvey Silverglate: I chose the term very carefully and intentionally. They are police. They don't have uniforms. They wear suits. But they are policemen, enforcing a federal criminal code that never should have been allowed to grow to what it is now.

Let me tell you why the Federal Criminal Code is so dangerous. The Constitution does not give the federal government plenary power to enforce criminal laws. The Constitution is very specific as to what federal criminal laws there should be. Piracy is one of them. Counterfeiting, for example. There's a particular federal interest in making sure people don't print their own dollar bills.

However, what's happened over the decades and centuries is that the federal government with the aid of the Supreme Court has enacted an enormous number of criminal statutes. Here's how it works: Federal fraud, for example, is essentially undefined. What the statutes say is any fraud that is committed through the use of the US mails, which gives the Feds jurisdiction from one state to the other. If you commit a crime and you travel from New Jersey to New York, you've federalized whatever it is you've done, or the use of the telephones or the mails or anything like that. In other words, the crimes are ill defined. As long as you operate with the use of the mails or in interstate commerce, you have committed a federal crime.

How do you define them? The federal government decides whatever it is that should be criminal this week, and that is the danger. There's a fundamental principle of English common law, that nobody should be prosecuted for something unless they knew what they were doing, intended to commit the crime, and the crime is readily defined. That is what has been lost in the federal system. So, we are all vulnerable, and that's the fundamental basis of my book Three Felonies a Day: How the Feds Target the Innocent. It's not substantively what you do. It's simply your use of the mails or the telephone, or the means of interstate communications or commerce.

You know the saying they can indict a ham sandwich? They can indict a ham sandwich as long as the ham sandwich gets on the telephone.

How Federalization of Crime Undermines Federalism

Bob Zadek: Harvey, you mentioned fraud, a wonderful place to start. Fraud is a crime, I predict, in every single state. So, somebody who defrauds another – or take any other crime – has committed a crime in a jurisdiction, which has a police force, which has a court system, which has a jail, and which has a prison, which can deal with it. So, if anything is felt to be criminal, the states know how to make it criminal. Can you give us a historical perspective on why anybody perceived the need to create a federal crime when it already was a state crime? Doesn't that violate federalism?

Harvey Silverglate: First of all, the thing about state criminal statutes, with the exception of Louisiana, the states all operate under the English common law system. What do I mean by that? I mean that the definition of these crimes – larceny, assault and battery, anything of that nature – has been defined by hundreds and hundreds of years of judicial decisions, and legal precedents. If you go into a supermarket and you steal a big bag of potato chips, that's larceny. And if you steal enough bags of potato chips, it's grand larceny. Everybody understands what stealing is. Everybody understands what assault and battery is.

Who understands what mail fraud is? It's a vague notion of fraud committed by the use of the mails. Almost everything we do – including this interview – the feds have control of what we do, and what we say because we are using means of interstate communication to conduct this interview. If one of us says something that can arguably violate a federal statute, suddenly we've got an FBI agent knocking on the door to doing interviewing. The interview process is another whole topic.

Bob Zadek: We'll get to that, but when we start with a system where bad behavior is covered adequately – at least in the opinion of each state looking at them one at a time… California says we are satisfied that using marijuana should not be a crime, and in our state, it should not be a crime. Nevada may reach a different conclusion. That's federalism in action. That's the way it's supposed to be. What was the process, going back a long time, when somebody in Washington felt a need to criminalize behavior, which the states had already decided either was or was not criminal? What caused the growth of a federal system of criminalizing interpersonal behavior where a state felt otherwise? How did we get down this horrible road we've gone down so far?

Harvey Silverglate: The problem is that the US Supreme Court, which could have stopped all this, has enabled it. It has bought into the notion that as long as you use the means of interstate commerce or interstate communication, what otherwise would be classic common law crime covered by the states, now becomes a federal crime. There was this whole era. Remember, we had the New Deal, for example. The Depression enlarged the scope of federal jurisdiction in American life. We had a national emergency. The Depression was very serious. And all of these programs that the Roosevelt administration started are credited with really saving the country in a way. There was some real revolutionary activity going on at that time. The problem is that the Supreme Court allowed this theory about increased federal jurisdiction to operate in the criminal justice system, which has turned out to be a tremendous threat to American liberty.

The common law notion of crime and punishment is that a person can be prosecuted and punished for knowingly violating a clear obligation. Now, we have a situation where you can get 10, 15, 20 years in federal prison for doing something that some prosecutor can convince some judge is a crime, for example, as long as you use the telephone or the means of interstate communication, or the mails. So, these are ill defined, undefined, and deracinated from common law definitions of what crimes should be. The common law is what ordinary people understand. A crime should be “punch someone in the nose,” “steal what's not yours.” But lawyers don't understand. I have cases in which a client is charged with something federally, and I think to myself, "What the hell? Why is this a crime?"

Well, it's a crime because some Assistant US Attorney and some FBI agents think they can convince a judge it's a crime. And mail fraud, again, what the hell is fraud? A lot of this is in the eye of the beholder. It's very dangerous to liberty to enable the government to pick people off who might be, for example, critics.

I have had investigations done of me, because I'm a kind of a loudmouth, high-profile, civil liberties and criminal defense lawyer, and they'd love to get me.

That's not a good formula for a free society.

How the FBI’s Broken Culture Originated

Bob Zadek: Now, we have a system of federal law – a Federal Bureau of Investigation, a de facto police force. But that's not how they present themselves. As you said, it's a culture that can't be fixed. So, tell us first what that culture is. Was it always that way from inception? Was that because of the leadership or is there something wrong with the very fact of it that makes it not curable?

Harvey Silverglate: I attribute it to J. Edgar Hoover. And remember, Hoover got to the point where he was able to blackmail presidents of the United States. He of course infamously tried to blackmail Martin Luther King, Jr. Remember, they planted a bug in a room where King was having an affair with a woman and threatened that they were going to tell King's wife unless he calmed down in his civil rights work.

They blackmailed John F. Kennedy because of Kennedy's affairs. This is an FBI director, who was able to blackmail the President of the United States. No wonder nobody ever fired him. He had dossiers on Congressmen. So, we allowed this monster to get an enormous amount of power. And he was able to do it, in part, because he could pin a crime on just about anybody, including members of Congress and occupants of the White House. This was a huge mistake to allow this director of the FBI to get to the position where he was in. But the problem was he had something on virtually everybody. Well, why? Because virtually anything that anybody did can be teased into the definition of a federal crime.

Bob Zadek: J. Edgar Hoover was able to accumulate so much power using not a gun but using information. Information is, incidentally, more powerful than a weapon, as J. Edgar Hoover has shown. So, one would think that an incoming president, incoming Congress, anybody in Washington, who feels that they could be the subject of that power against them, why wouldn't they seek to have an FBI head who was clean, who was not a threat, who was more bureaucratic, who was not ambitious to accumulate power through information? Because I presume from what you have said that successive heads of the FBI after J. Edgar Hoover were the same. Well, how were they able to be that way if the people who will hire them are fearful of the power they could accumulate?

Harvey Silverglate: Well, first of all, I don't think any FBI director since Hoover was nearly as bad as Hoover. But the problem is you could have the Archangel Gabriel as the director of the FBI and it wouldn't change things at all, because there is an ingrained culture that operates in the FBI that is beyond the control of the director. The director really now is sort of like a bureaucrat. The agency operates pretty much on its own. And that's the problem. You can find good directors. If I thought that that would do the trick, I would say the solution is to have good director. But culture is beyond the ability of any director to change, and that's why I think abolishing the agency and starting over with a new name, new agents, new director, whole different ball of wax is the only solution.

The Corruption of Form 302

Bob Zadek: Now, give us the bullet points of the elements of that culture that you are referring to and support that explanation with examples, because I dare say there are many that are available to the public, and certainly you are aware of a great deal of them.

Harvey Silverglate: Okay, let me tell you what happens. When the FBI knocks on the door of a client of mine, I have told all my clients that if they show up, give them my name and phone number and don't say anything else. So, the agents contact me, "We would like to interview your client."

I say, "Sure. Come up to my office tomorrow at 3:00."

"No, we'd like to do it in our offices."

"Well, that's too bad, then we're not going to show up. Either you show up in my office or it's not going to happen."

So, they show up. Two agents show up. One of them takes notes. The other one asks the questions. The one who takes the notes then goes back to the office and types up a report of the interview called the Form 302. That report is the official record of the interview. I have never seen a Form 302 that accurately depicted what was actually asked and said. It depicted what the agents hoped my client had said in answer to their questions.

So, I say to them, "Okay, I'm alright with this. I pull out a tape recorder."

I put it on the table. I press “on.”

And I say, "All right, let's go."

The agent says, "No, no, we're not allowed to have a tape going."

I say, "Oh, really? No kidding. Well, my client is not going to be interviewed unless I am allowed to record it." And the agents get up and leave, bye-bye.

Now, can you possibly think of one good reason why an agency would have a rule that interviews are recorded only by an agent taking notes, and if you use electronic recording means, they get up and walk out? There is only one explanation, and that's because they are not interested in an accurate record of the interview. They're interested in having a record of what they wish your client had said. And in fact, if the 302 is the only evidence of the interview, that's what your client has said. This is a totally, totally corrupt process.

Robert Mueller was a US Attorney in Boston. I know Mueller very well, and he knows me very well. I would not say that we like each other too much. He is now retired. When Mueller testified before a congressional committee, one of the questions brought up by Representative Emanuel Celler of Brooklyn, was why we don't have recordings of FBI interviews.

Mueller said, "Well, it would interfere with the ambience of the interview."

The ambience of the interview!

"We've done very well with the Form 302 process. We don't need it.”

And Congress just folded its hand. Now, why did they fold its hand? I think congressmen are afraid of the FBI. And that's the problem. The FBI has material to blackmail an awful lot of them. And that's the problem. The FBI is sacrosanct in its own power base. It is incapable of being controlled. That's the problem. Can you imagine Mueller, who's an intelligent guy – a Princeton graduate – I really don't think he convinced, I think they were intimidated, that recording was not necessary, given the history of this corrupt agency.

Bob Zadek: Let's follow through on that story you told us about your client or another who witness submits to an interview – not an examination under oath and that's really important. It's not perjury. It's an interview. It's a chat with somebody who happens to be employed by the federal government. And the FBI agent, the one writing on the pad, records what he thinks he heard or what he wants to have heard.

Now later in time, that 302 Form finds its way into the public record to be explained maybe in the course of an examination later on. And the witness says, "I didn't say that. And in fact, that's wrong. That's not what happened."

Now, tell our audience what follows from the witness saying to the institution of the FBI, "I didn't say that," or, "That's not accurate," because a lot of unpleasant consequences flow from that.

Harvey Silverglate: The unpleasant consequence is that the witness is indicted. Why indicted? Because it is a federal felony to lie to any employee of the federal government. By the way, not only FBI agents, if you lie to your postman – he's a federal employee – that's a federal felony.

What Feds then threaten you with is, "Okay, you said something that we say you didn't say, or you're going to deny that you said something that we claim you did say under the 302 form, so,this is a violation of 18 U.S. Code § 1001. It’s a felony to give a false statement to an agent. So, that means you lied during the interview, and you've committed a felony. You say you didn't lie? Well, we have Form 302 that says you did, and you don't have a tape recording to prove otherwise."

So, it's a perfect system. Talk about putting words in a witness's mouth, that's exactly what they do. It is a pernicious, pernicious system.

“Culture is Everything”: Why Abolition is the Answer

Bob Zadek: Now, clearly you wouldn't be writing so much, and with so much information and passion, about one bad practice – that they don't record interviews. The problems, as you have explained from firsthand experience, are much deeper and much more pernicious than merely that. ‘Abolish' is mighty strong language. So, what are examples if there are others or reasons? Because if you're trying to persuade the country to abolish a revered (by many) institution, which has been around for a long time, most Americans would say, "We're kind of happy we have an FBI, it protects us."

Harvey Silverglate: Well, first of all, it isn't so simple to get a statute for recording enacted. We tried it, and the FBI managed to convince the Congress not to do it. How did they manage to do that? Well, there are a lot of explanations for that. One of which is any Congressman voting against the FBI is thought to be “soft on crime” – not that good on law and order. The second is that the Congress is afraid of the FBI because they can pin a crime on virtually every congressman – I’m not saying congressmen are all corrupt, I’m saying the federal criminal system has these vague broad statutes that can indict a ham sandwich, and the ham sandwiches are afraid of the butcher. That is exactly one of the problems.

So, the FBI basically terrorizes the people who in theory are supposed to be controlling it, and it has its own institutional power that even has presidents nervous because, of course, presidents can be investigated because of the same ham sandwich problem. The presidency is an incredibly complicated job. Arguably, a president commits three felonies a day, and it's the FBI that decides which felonies to investigate. So, it is an institutional problem here.

I do not believe that the FBI is capable of reform, because it's been going on since the first decade of the 20th century when the FBI was started. I'm not sure if I've quite answered your question, but culture is everything.

Profiles in FBI Abuse of Power

Bob Zadek: Tell us a bit about some of the more recent examples.

Harvey Silverglate: One of the most high profile was the blackmailing of Martin Luther King, Jr. Hoover hated King and he was trying to derail the civil rights movement. He had the FBI illegally bug a hotel room where King was having an assignation with a young lady. Then he let King know that he had this recording. Now, can you imagine that this happened in the United States of America? So, there is an example that in my mind stands out.

Now, let me tell you a more personal example. I had a criminal case about 15 years ago, in which I represented somebody who is high profile. I can't go into the details because of attorney-client privilege. But it was a high-profile corruption case in Boston. At the time, Mueller was the US Attorney in Boston, and I learned years later that the following had happened.

Two agents were stationed outside my office building. Their instructions were to follow me everywhere. One day, a guy comes out of my building – 88 Broad Street – and the agents think that it's me. Turns out it's not me. This is lunchtime. He has an office in the building, he works in the building. He goes to a parked car underneath the then-elevated southeast expressway, gets into the car, and he is given oral sex by a woman who's behind the steering wheel. The agents are thrilled, and they write this down. I don't know whether they took pictures or not. About three or four years later, a criminal defense lawyer friend of mine tells me that he was engaged in discovery in his case, and he came across this report that the agents had written in the file about Silverglate getting oral sex from this woman during the lunch break. In other words, they had this in case I gave them trouble. They could then blackmail me, essentially. Can you believe that this happened? This was not in Russia. This was not in Turkey. This was not in one of these authoritarian countries. This was United States of America. And it wasn't even me, of course. So, that's one story.

Let me tell you another story. This is all personal, now.

At the time, my law partner was Nancy Gertner, who later became a federal judge. Silverglate & Gertner was the name of the firm. She is now a professor at Harvard Law School. We had amarijuana importation case criminal case together. We get a call from somebody who says, "I have information that can exonerate your clients."

So, we said, "Come on in."

So, we lead this guy into a conference room. In the conference room is Gertner and Silverglate and the witness. The witness then says, "Actually, it's not true that I have information that will exonerate him. However, I like your clients. I am prepared to testify falsely. And this is what I'm prepared to say." And he goes into his rap. Gertner and I stand up and say, "We're sorry, but it's a crime to suborn perjury. It's a crime for you to perjure yourself. It's a crime for us to cooperate in that process. Would you kindly leave?"

He's surprised, he gets up, he starts to walk out. And I noticed there is a lump over his suit jacket in his right shoulder. It was a small back then, they were not as miniature they are now. He was recording the conversation so that if we had agreed to it, we would be indicted. I later complained to the US attorney about it, Mueller. Mueller had the nerve to say to me, "Well, we had information that you might have wanted this witness to perjure himself, and we had an obligation to follow it through." Can you imagine?

Bob Zadek: This is entrapment.

Harvey Silverglate: Yes, we're perfectly honest lawyers. We've never had a disciplinary charge against us. I've been doing this for 53 years, and I have a clean record. And yet, they tried to do this to me. Well, after a while, you can't be cynical enough.

The Vicious Symbiosis of FBI Overreach and an Oversized Federal Criminal Code

Bob Zadek: You are one of the public figures, but by no means the only one, who supports the thought of abolishing (strong words) the FBI.

Has anybody of any power indicated support even if they couldn't do so publicly? Is there a below-the-surface acknowledgment in Washington that this is something that needs to be fixed?

Harvey Silverglate: Quite a few federal prosecutors have confided to me that they're shocked by the dishonesty of the FBI agents. They cannot, however, say much in public, or at least they're not willing to sacrifice their careers to do so. A couple of federal judges have told me that they agree with me. Quite a few law professors. So, there are people who really know the system who agree with me, but because of Congress, this is not going to happen – at least not in my lifetime or in your lifetime.

I attribute part of the grip that the bureau has on the Congress because the Bureau has so much on so many congressmen. Remember, this is not a comment that's intended to say the congressmen are corrupt. Because remember my “three felonies a day” thesis: you can pin a federal crime on just about anybody. So, the Bureau has this great device that it can use to certainly blackmail the people who is supposedly in charge in this country – that is the Congress – because congressman are engaged in busy lives. They engage in a lot of financial transactions. They are busy, active people who are susceptible to being charged with a federal felony. So, this is a symbiosis between the Federal Criminal Code and the Bureau, and it is a vicious symbiosis.

Bob Zadek: The very existence of an extensive system of federal criminal law, where federal criminal law does nothing other than duplicate the same behavior as being criminal that has already been criminalized by the states. That is to say, there does not appear to be any need for a federal crime if the same act is criminal under state law. If the purpose of criminal law is to deter bad behavior and to punish those who engage in bad behavior, those goals of criminal law are satisfied by state law.

Harvey Silverglate: Correct.

Bob Zadek: Wow, there's nothing like detecting the total absence of a need and then filling it.

Harvey Silverglate: It's worse. You understate the problem and let me tell you how. Massachusetts has long ago, decriminalized marijuana. The federal government continues to maintain that the use of marijuana is a felony. In the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, the state legislature – having decided that smoking or selling marijuana is not a crime – one can still get busted by the Feds for doing something that the legislature of the sovereign Commonwealth of Massachusetts has decided is not a crime is a crime.

So, it is a terrible violation of the rights of people in this state that the feds override, because if there's a clash between state and federal law, federal law controls. Why should the Feds be able to do that? The answer is because we have destroyed all notions of federalism, and because we allow the federal government to criminalize the kinds of activities that the founders did not intend for it to have jurisdiction over.

Bob Zadek: Now, let's remember that when our country was founded, the police power – i.e., looking after the health, welfare, and safety of citizens – was universally acknowledged within the country as the province of states. Why? Because criminal law reflects the public's concept of right and wrong, and that's a private decision. People in different parts of the country could have a different opinions of right and wrong, and it's very uncomfortable to have one citizen in another part of the country export their morality to another citizen in another part of the country.

Marijuana or drug regulation is a perfect example. The state has the power to conclude that our population or a majority opposes the use of narcotics, that's okay. Federal criminal law by its very nature is anti-freedom because it removes from citizens of one state the freedom to enact laws that they are comfortable with, and in a country with as many people as we have, with as complex a civic life– as complex a way of living– exporting one worldview to another part of the country cannot work and just invites divisiveness. So, Harvey's book, which was written two decades ago, stays relevant today – maybe moreso because we have more federal criminal law than it was when it was written.

Harvey's book is Three Felonies a Day and the premise is that the average American, whether they know it or not, going about their daily life is probably committing three felonies a day. Is that a fair summary of the book?

Harvey Silverglate: That is a fair summary of the book. I also want to point out that this problem of federal overreaching is really a result of the Civil War. Slavery has had a terrible impact on this country in a lot of ways. That still lives with us today. However, the notion of states' rights has been blackened and given a bad rap, because the southern states kept slaves. However, that doesn't mean that states should not have powers and rights that the federal government doesn't interfere with. Slavery was really responsible for the destruction of federalism in this country.

Bob Zadek: That's a wonderful way to point out the issue that the power of the states as opposed over its people, as opposed to the power of the federal government, that worked fine but for slavery. There was no other issue where it was felt we needed a national law. No, we never felt a need for national law governing speed limits or driving age or use of alcohol, or the use of drugs. There never was and never will be a need for national rule. It can be regulated at the local level, which promotes freedom.

Harvey, you have a very ambitious undertaking to persuade the country to abolish the FBI. But in doing so, you are performing an important public service because that organization is failing us in many, many ways, and it has tools for its own preservation that other federal agencies don't have, as you have explained.

I found myself thinking about the CDC in its performance during COVID. The CDC was created to provide the public with information and research involving communicable diseases. Its last official act in COVID was a national eviction moratorium. Oh, my goodness. So, agencies have a way, if they're not examined, to suffer – they decline, they expand their goal, they become inbred. The very purpose might have been laudatory but nobody can even remember why these agencies were formed, including the Federal Bureau of Investigation, aka our uninvited federal police force.

So, Harvey, thank you for helping us pay attention when we read the headlines. Now, we can look behind the headlines and ask ourselves, "What is this headline really teaching us."

Harvey Silverglate: Thank you for this opportunity to talk on these subjects.

Harvey Silverglate: I have, is the best way to find what I've written.

Bob Zadek: Thank you so much to Harvey, and thank you so much to my friends out there for allowing me to have an hour of your attention on this day and I hope you enjoy the rest of the weekend. Thank you so much.

Harvey Silverglate: Thank you.

Share this post